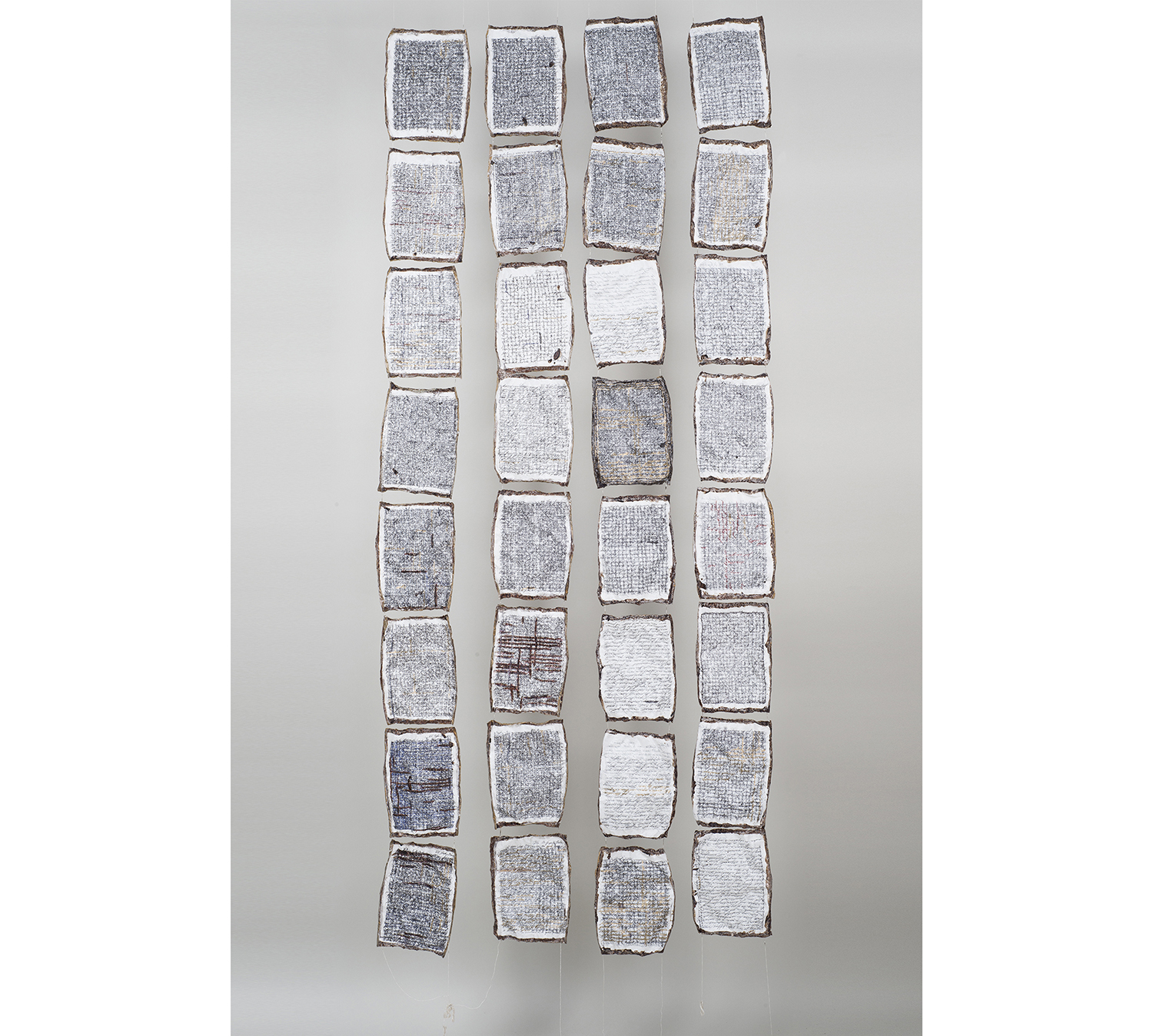

A SECRET HISTORY

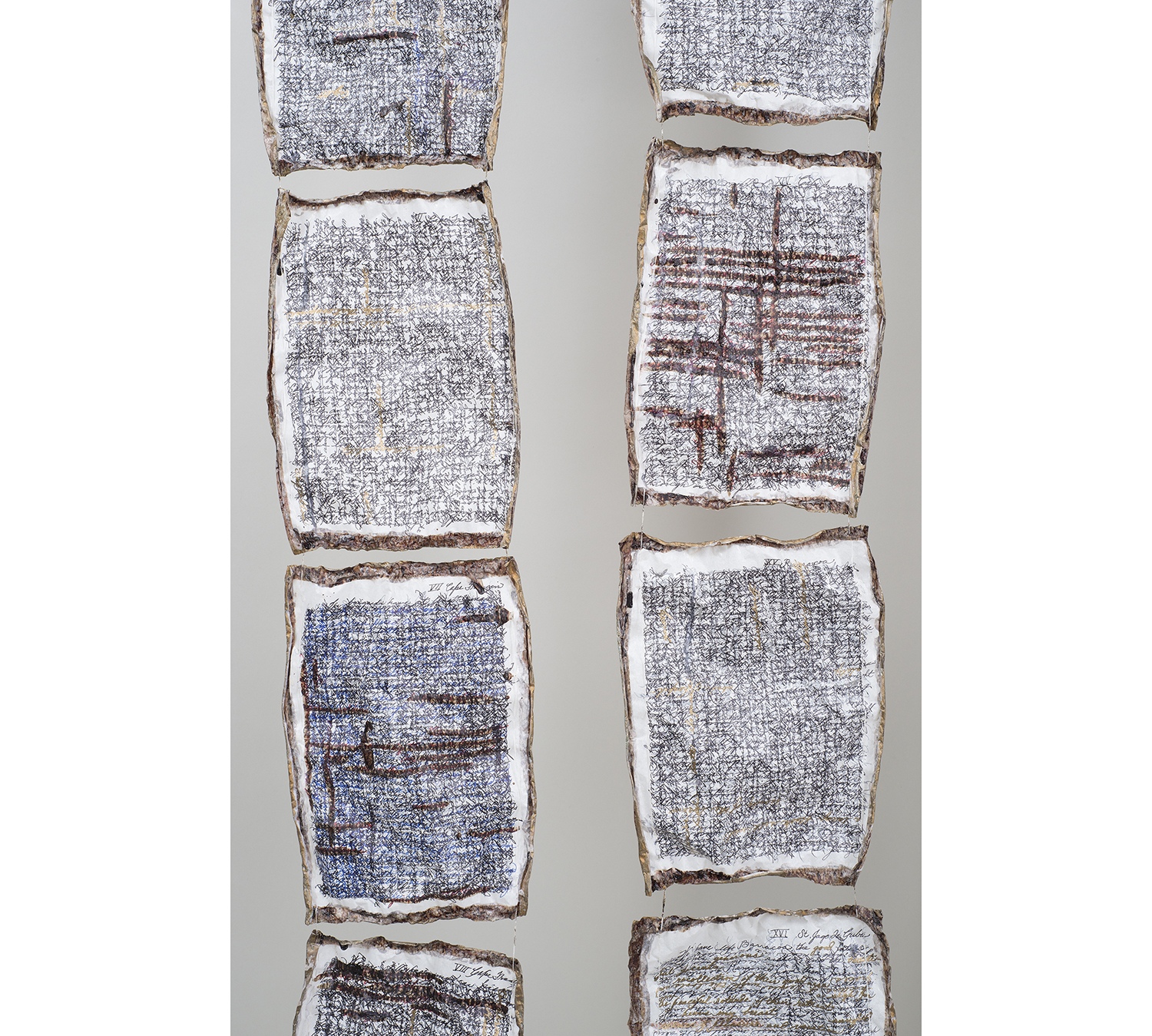

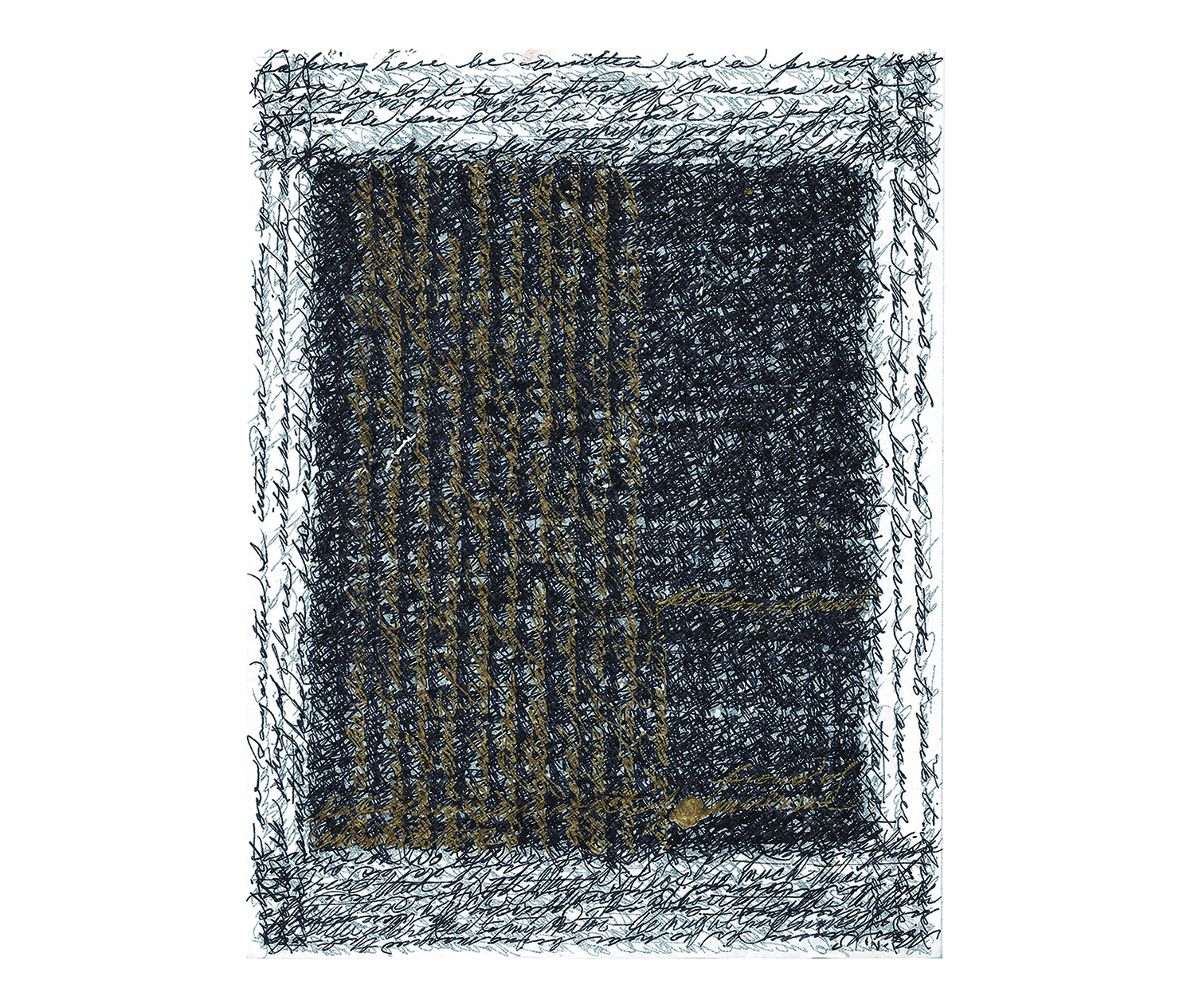

Comprised of 32 fictionalized letters, “written” –in her own words – “in a light, pretty style” to her “mentor,” Leonora Sansay’s Secret History ties the Haitian to the American Revolution through an equalitarian perspective of nascent feminism. Black revolution triggers her liberation from the marriage Burr arranged for her to alleviate the distress of the embarrassing condition her fiancé left her in when he died.

Slaveholder Louis Sansay, like Stephen Jumel deposed from his Saint Domingue plantations by revolution, makes the best of a bad situation selling his property to the revolutionary Toussaint L’Overture on his way out. New to the mainland and seeking influential counsel, he hires Burr, then the Senator from New York, in Philadelphia. Beyond legal and business consultations, Burr advises Sansay to marry Leonora, the “too well know” innkeeper’s daughter, his confidante, mistress and, in this case, political operative.

Sansay returns on June 7th, 1802 to usurp the Haitian property he had sold, coincidentally same day as L’Ouverture’s arrest and deportation to France, where he will starve to death in a dungeon. Chronicling Napoleon’s failure to re-enslave Haiti, Leonora’s The Secret History ties her struggles with a jealous, abusive husband to a Burr-esque agenda opposing racial/caste distinctions, a chauvinistic agenda and imperial hubris.

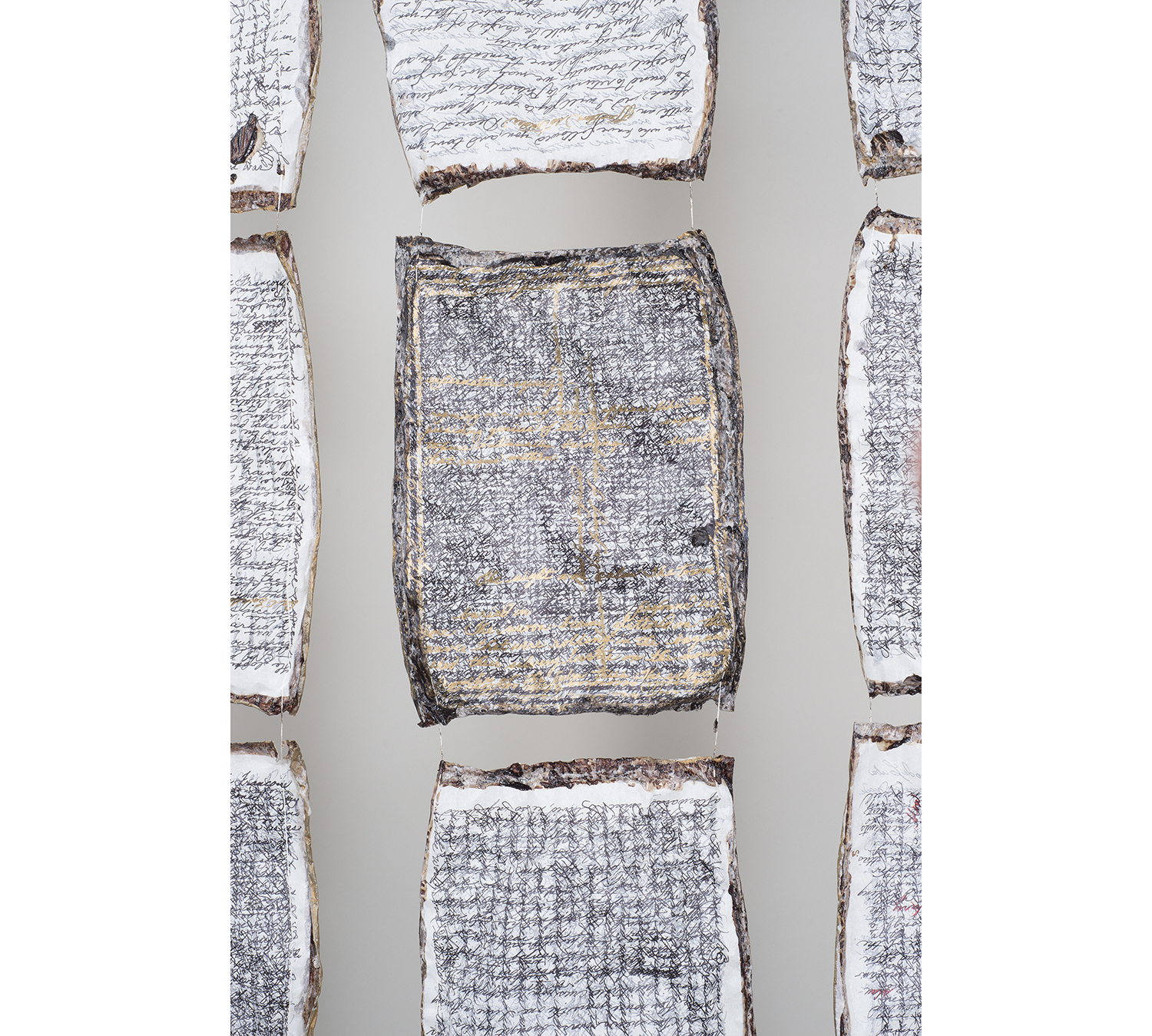

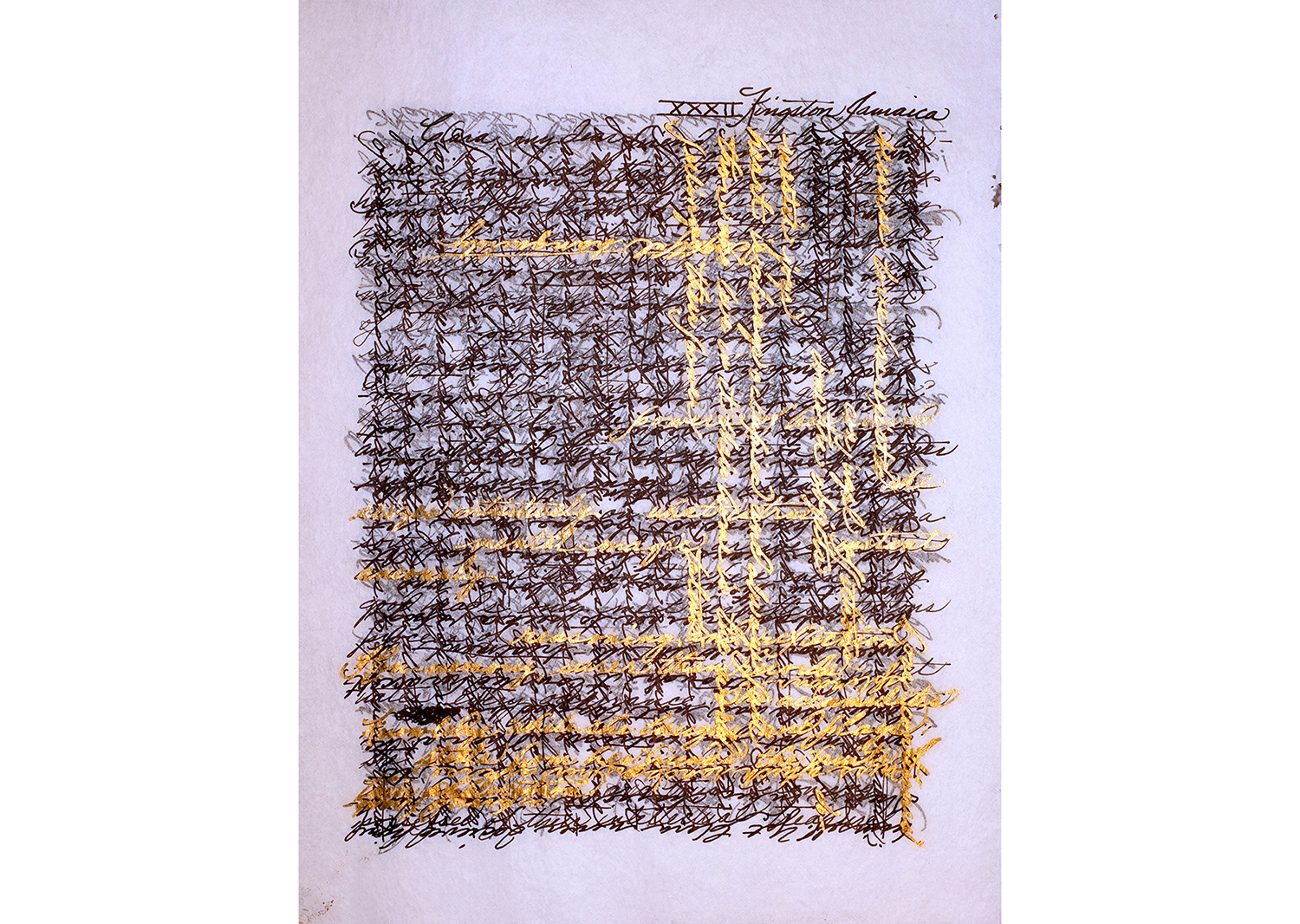

The Secret History exemplifies the opposition of revolutionary egalitarianism to Imperialist partisanship contrasted with women’s domestic/sexual encounters. In one scene from her roman à clef, a woman cuts off the head of her husband’s black mistress and serves it to him for dinner. Juxtaposing the baroque opulence of Cape Français with her first hand account of the brutal triumph of the black in a revolution for racial equality, passages of the transcribed letters are highlighted in gold, framed in blood, and sugar coated – ironically called refined.

Transcribed cross-written letters on onionskin paper, ink, blood, and sugar