Arts of Beauty Exhibition Concept and Direction: Camilla Huey

Arts of Beauty Exhibition Curated By: Jasmine Helm

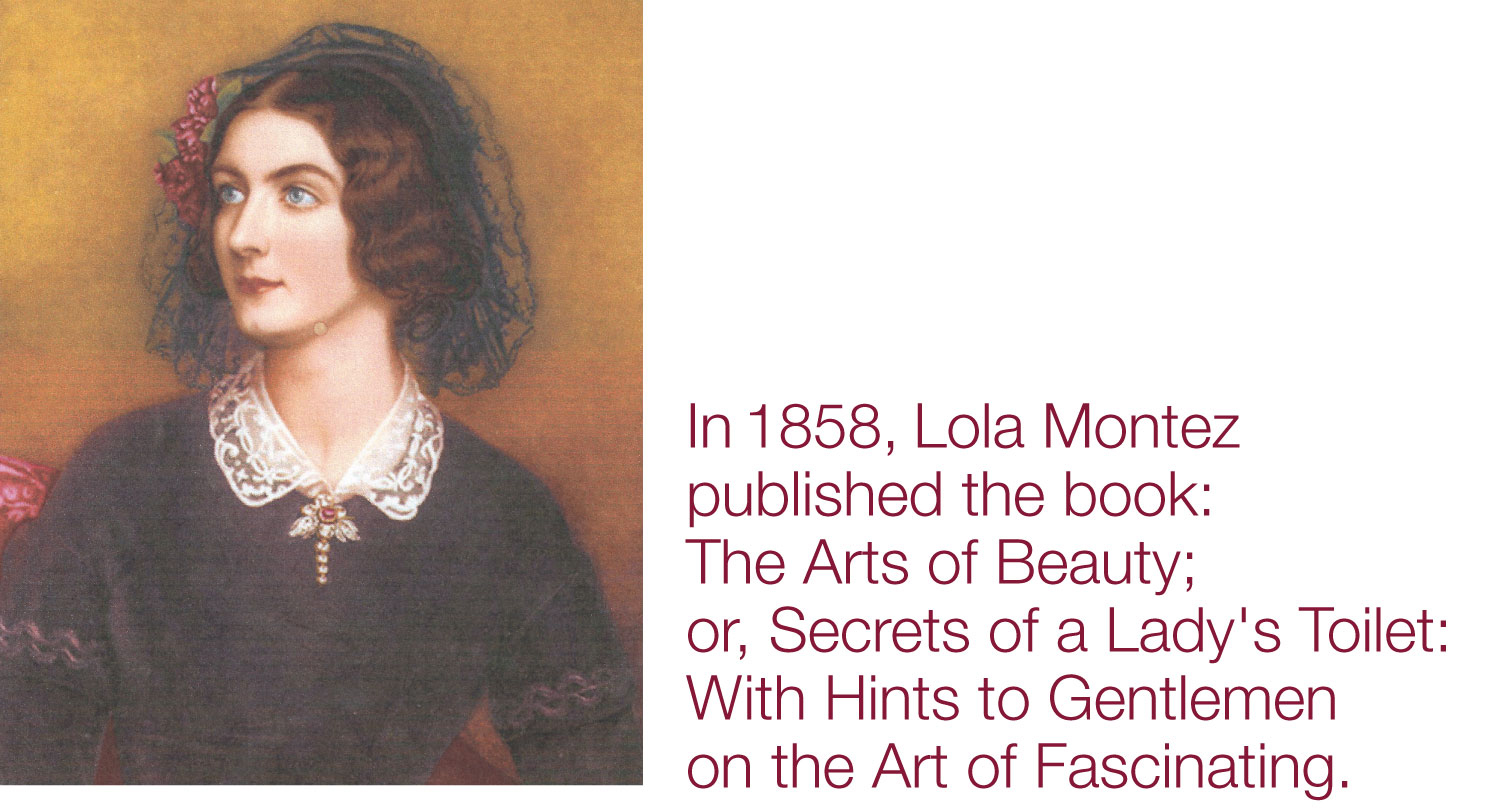

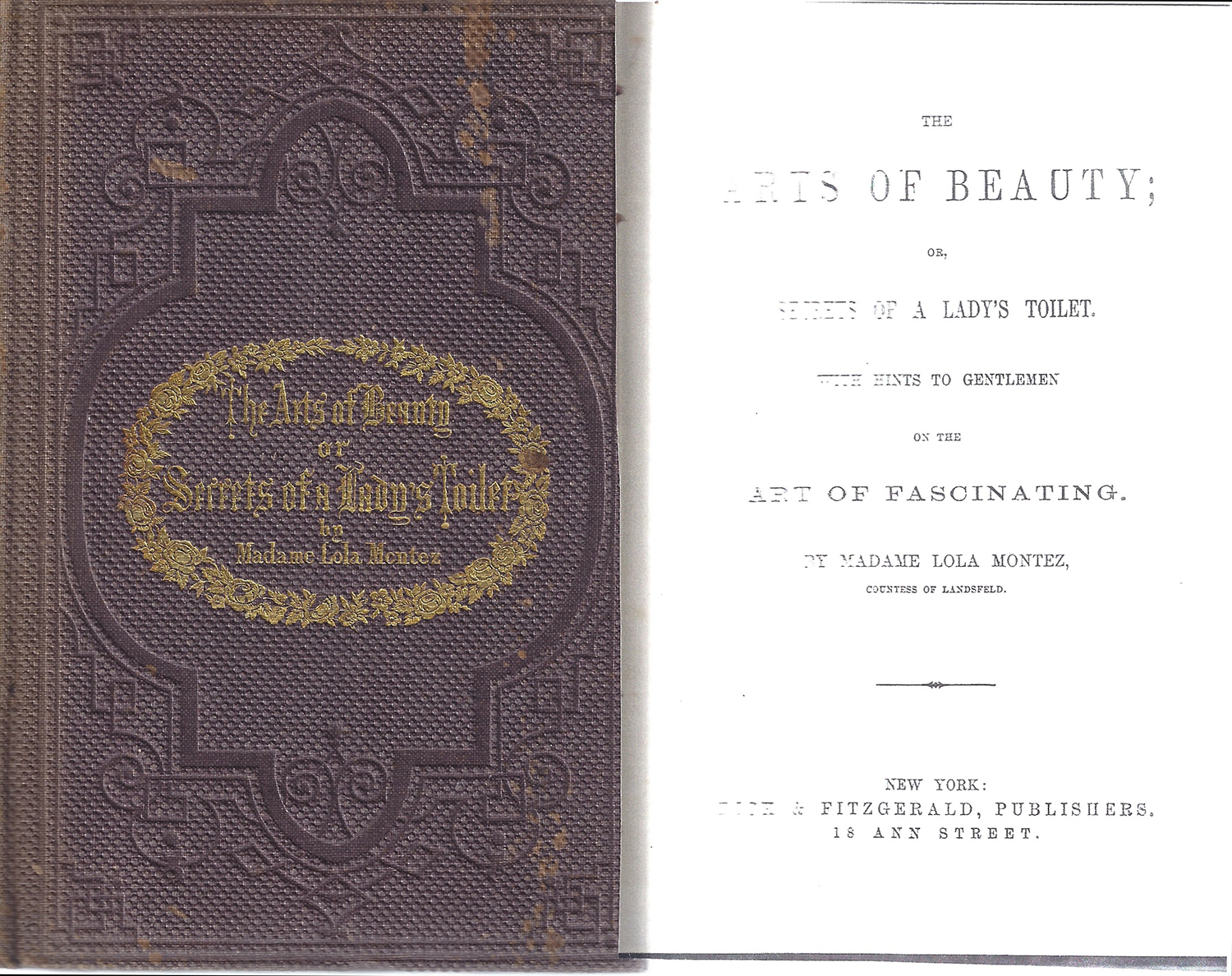

Instructing women on how to preserve their charms. Lola Montez believed that beauty was a woman’s most important quality; stating, “My design in this volume is to discuss the various Arts employed by sex in the pursuit of this paramount object of woman’s life.” The exhibition The Arts of Beauty: Feminine Dress and Adornment, 1774–1865, will investigate the central role beauty played in the lives of women, especially in high society, by analyzing the women’s toilette, dress and accessories, three components which were essential in the creation of a lady’s image. During the 18th and 19th century the lady’s toilette held a ritualistic importance; simultaneously, her clothes and accessories communicated her taste, status as well as dictated manners and customs. The exhibition includes over twenty objects from The Morris-Jumel Mansion’s permanent collection to illustrate the importance of feminine beauty and adornment during the period.

The Toilette

Toilette or toilet refers to the act of grooming, getting dressed, the place in which a person dressed themselves, and dress attire. In Europe and the United States, the lady’s toilette was where she prepared herself every morning—it was a space of ritual, intimacy, performance and display. In the 18th century, for royal and upper classes, the toilette was conducted in two parts: the first part was intimate, consisting of basic grooming; the second half of the ritual was public, as ladies would entertain family, friends, and attendants while dressing. The act was often associated with coquetry. Over the course of the 19th century the toilette was increasingly focused on upholding standards of propriety.

The toilette often took place in a dressing room called a boudoir—a smaller room adjacent to a woman’s bedchamber. Eliza Jumel’s dressing room is an example of a wealthy woman’s dressing room during the 19th century–the furniture and decor matches that of bedchamber and is an example of Empire Style, it showcases her admiration for French art and decor. Toiletry items such as the tortoise shell comb, hand mirror, essence bottles, and laces would have been displayed on the vanity. These decorated objects served functional purposes and displayed a woman’s preference for finery.

At the vanity, women would groom their face and hair. In order to maintain beautiful hair and complexion a variety of recipes for facial cleansers and moisturizers existed made from natural botanicals. The recipes were printed in lady’s journals and books such as Lola Montez’s The Arts of Beauty. In the 18th century cosmetics were commonly worn. In the 19th century, a proper lady did not wear rouge on her lips or cheeks, cosmetics were reserved for courtesans and female performers. Powdered wigs were worn in the 18th century, then in the 19th century various styles of more natural hair were in vogue.

The final phase of the toilette consisted of dressing the body. It was difficult for women to get dressed independently due the many layers of garments, the assistance of another person such as a relative, servant or chambermaid was necessary. If a woman was receiving intimate visitors during her toilette particular clothing was required, for example in the 1800s it included at morning dress with an elegant chemise gown and half-corset. The Gentleman and Lady’s Book of Politeness, Manuel complet de la bonne compagnie (1833) strongly advocated against “disorder of the toilet” in order to uphold duties of propriety, which “requires that you always be clothed in a clean and decent manner, even in private, on quitting your bed, or in the presence of no one but your family.”

Dress

In both the 18th and 19th centuries clothing communicated a woman’s status, personal style and created an image of elegance. Fashion changed rapidly, emulating styles worn by royalty and people associated with the upper classes, then was disseminated through the circulation of fashion dolls, plates and lady’s journals. The preference for beautiful dresses remained steadfast among fashionable women throughout the two centuries.

A variety of undergarments shaped the body into the fashionable silhouette and supported voluminous gowns. In both centuries, the primary garment that women wore was a chemise—a long white linen gown. A corset would be worn on top of the chemise gown and shaped the upper body. A corset was a woman’s most important undergarment, it supported, protected, eroticized her body. In the 1700s underwear was not worn for the lower body. Layers of petticoats were held up by a panier–a skirt hoop. Women began wearing drawers around 1806. Petticoats continued to be worn in the 19th century adjusting to changing silhouettes. In 1855 the crinoline cage appeared, creating a bell-like shape to the skirt. In order to uphold the demands of fashion and society women had to wear the appropriate undergarments to maintain the ideal shape of a particular period.

Stockings were made of silk, cotton and wool. The stockings in the MJM collection were owned by Eliza Jumel, they feature elaborate embroidery and decorative eyelets. Although, decorative stockings were considered improper, they were highly fashionable and frequently worn by women. Garters held stockings up. They generally consisted of a piece of ribbon tied around the leg above the knee. Garters have held erotic connotations for centuries and were exchanged as gifts between lovers. From the 1770s into the 1800s garters were highly adorned—frequently embroidered with amorous sayings. During the French Revolution, they were also decorated with political messages, the trend traveled throughout Europe. The garters on display are embroidered with the words amor y gloria translating into the phrase “love and glory” embodying both amorous affection and patriotism. These garters are a variation of the “Spring-band Garters” invented by English dentist Martin Van Buchell in 1788. Metal coiled springs were placed in garters in create elasticity.Dresses usually consisted of a separate bodice and a skirt. The creation of a dress was a collaborative effort between a woman and her dressmaker. Together they chose the fabric and embellishments; in addition, the dress was fitted, therefore garments from these eras are highly personalized to the wearer. Throughout the 1700–1800s, luxurious fabrics such as satins, fine muslin, taffeta, and laces were highly coveted and used for dresses. The quality of the textile generally indicated a person’s wealth. The featured bodices were likely worn by ladies from high society. Although the white satin bodice belonged to a young girl, it is an example of the prevailing slim silhouette during the first quarter of the 1800s, exemplary of Neo-Classical style. It was a high-waisted dress and would have had a skirt made from the same fabric. The printed striped purple and white floral bodice imitating chiné was also part of an evening dress dating from the 1850s. The skirt would have been made from the same textile and supported by petticoats or a cage crinoline. The wearer may also have been of the French persuasion as lilacs were commonly associated with Empress Eugénie. The Morris Jumel Mansion houses skirt panels and flounces from one of Eliza Jumel’s dresses. Jumel was highly fashionable, her favorite color was yellow and she often favored the combination of yellow silk and black velvet or lace. Etiquette journals and books advised against decorative dresses, yet fashion plates and clothing attest that women during these periods favored ornate garments as vehicles of expression and objects of beauty.

The appropriate dress for each function was of utmost importance in the 1700s and 1800s. Rules associated with dress became increasing rigid in the 19th century. Women were sometimes expected to change up to three times a day, which consisted of a morning, afternoon and evening dress. Maintaining social dress codes was of vital importance if a woman wanted to be perceived as a poised and beautiful lady.

Accessories

Accessories completed a woman’s ensemble and provided an additional outlet for adornment. A financial record from the Jumel family in 1805 lists a variety of imported accessories. Lace lappets ebbed and flowed in fashion in both centuries. In the 18th century they were worn as two streamers pinned to the hair. Lappets were made as a single piece of lace in the 19th century. The lappet in the exhibition is an example of Duchesse de Bruges Belgian lace and was worn by Eliza Jumel in the painting by Alcide Ercole, 1854, it signifies Eliza Jumel’s love of finery, while creating an air of historicism. Decorative objects in the 19th century frequently historicized styles from the past. This fan is exemplary of 19th century Roccoco revival style. The fan’s importance as a communicator of luxury and coquetry was established in the 18th century and continued into the 19th century. With the rise of machine lace in the 1900s gloves and mitts were in abundance—a strict decorum dictated the wearing of the accessory. Ladies were generally required to wear gloves in public and during visits, only to be taken off in the home with close friends and family. Short white gloves and mitts were commonly worn in the day. The style of shoes changed from one period to the next. Heels were preferred in the 18th century and slippers came into vogue after the French Revolution. Handbags had an evolving presence. In the 18th century women had pockets in their large skirts which permitted them to carry items and perhaps a pocketbook such as that on display from 1774. With the rise of the chemise gown in the last decades of the 18th century, women began to carry a small purse called a réticule. It held essential items such as a fan, letters, money and an essence bottle. The purse would have originally been worn hanging on the wrist. Susan Hiner (2011) theorizes that the rise of the handbag in the 19th century can be read as a sign of modernity and evolving female autonomy as women were increasingly able to carry their own money and participate in the luxury market.

Dress and adornment was a significant aspect of a woman’s life throughout the 19th and 18th centuries. The objects and toiletry methods that a woman chose to beautify herself were extensions of her personal aesthetics, reflective of societal values, and constructed an image of feminine refinement.